Have you ever wondered how National Parks happen? Who decides to when to protect wild nature? Where? Why? This website explores some of the most majestic natural areas in South America to provide varied perspectives that give possible answers to these questions and many more.

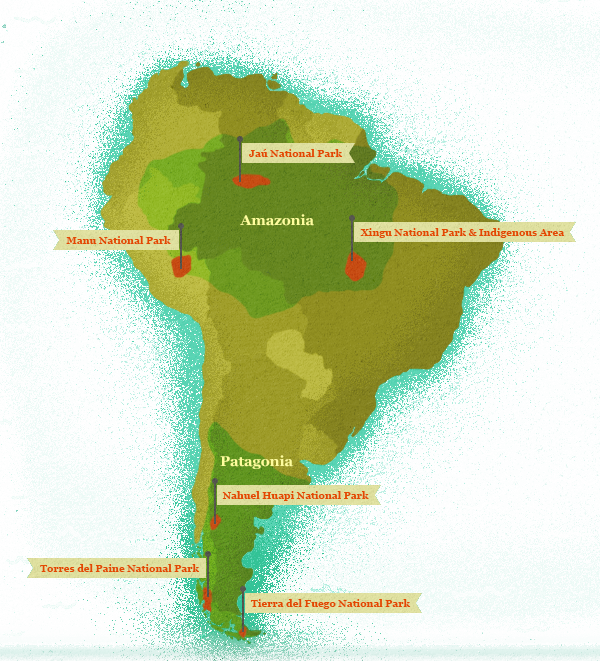

One important pattern that emerges is that natural field science and conservation grew up together in the two paradigmatic ecological and cultural regions of Patagonia and Amazonia. These environments have direct bearing on the world’s climate system, the regulation of carbon in the atmosphere, and the preservation of species ranging from ferns to felids. Importantly, they are also home to tens of thousands of native peoples (including the Mapuche, Yaghan, Xingu, and Matshigenka), and hundreds of thousands of mixed-race and European settlers. Together, science and conservation have indelibly shaped South America, a continent that today reserves more than a fifth of its territory in some form of protected natural area.

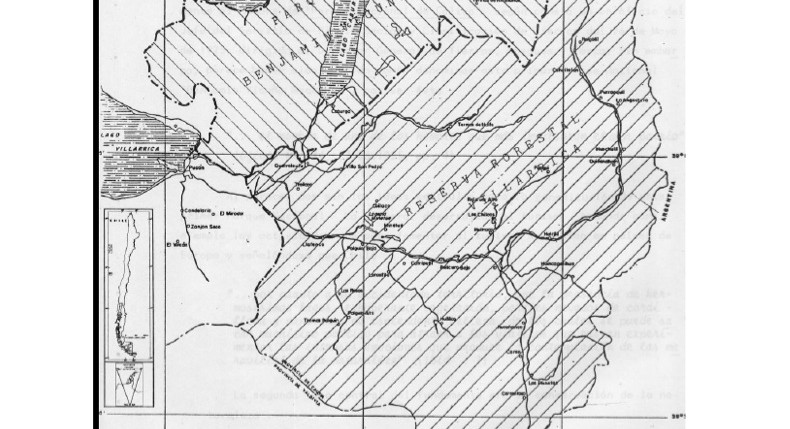

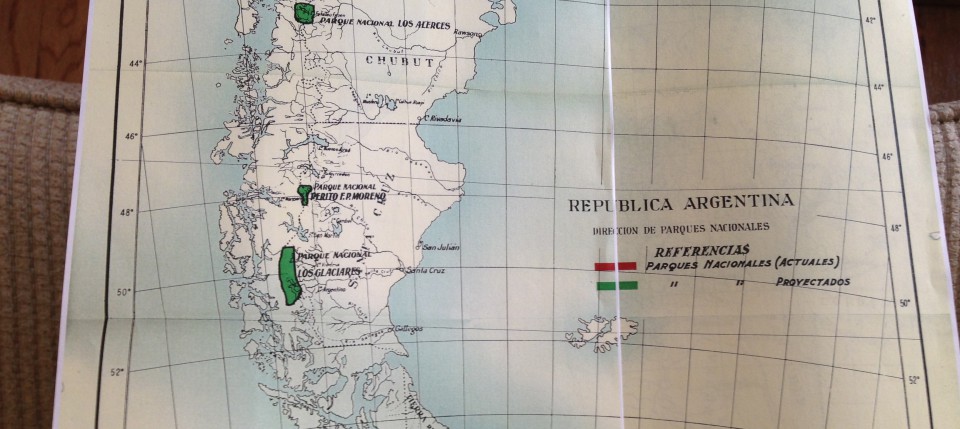

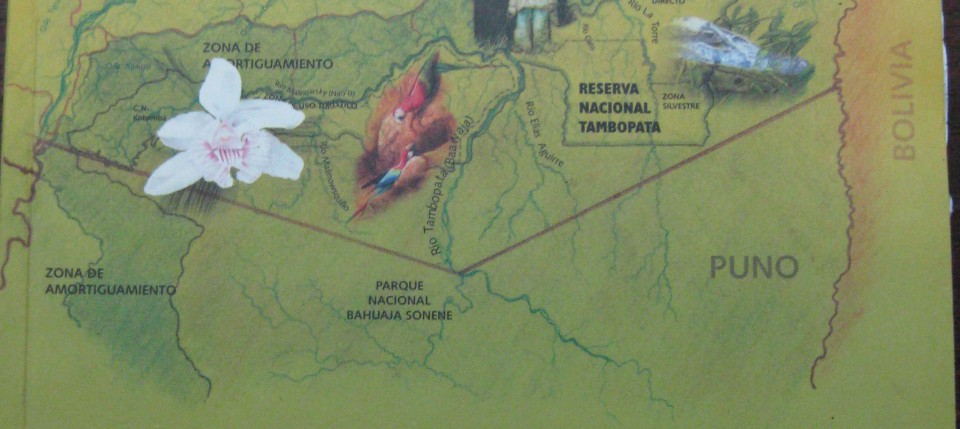

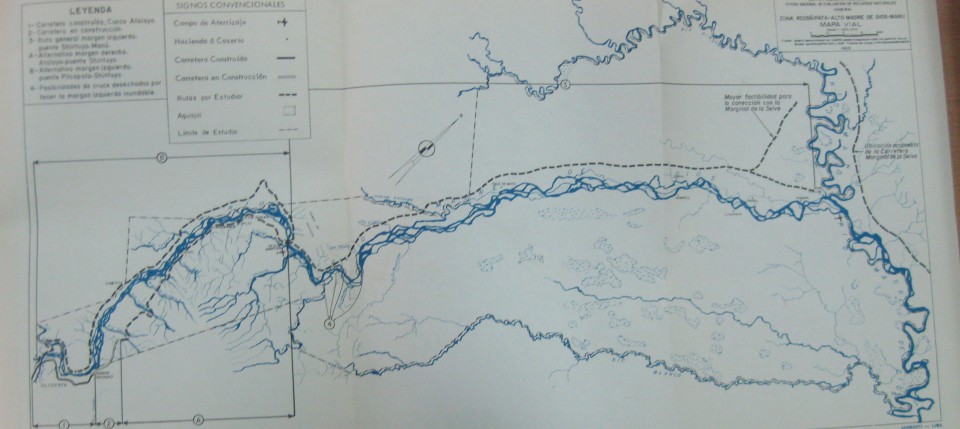

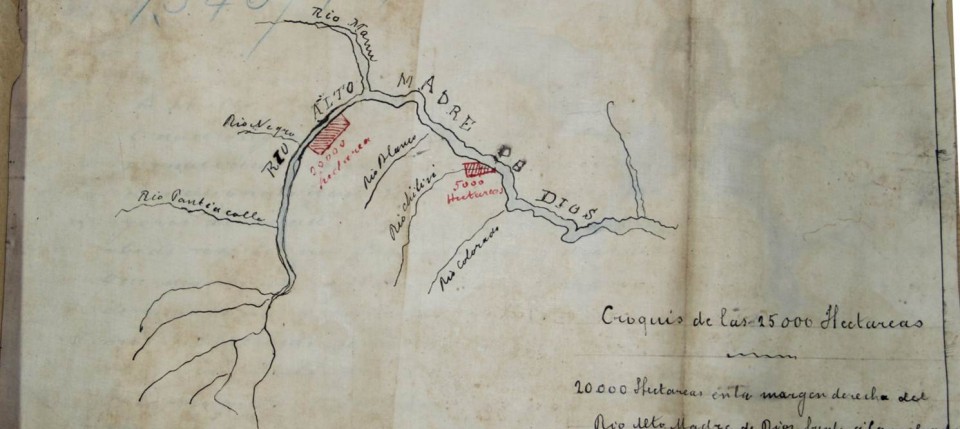

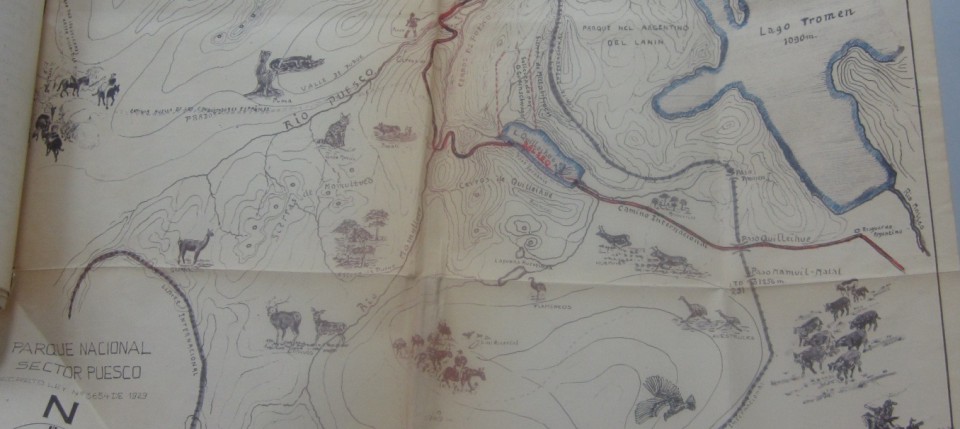

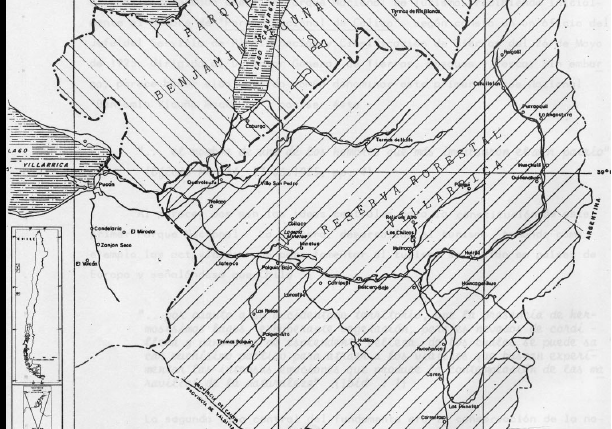

Another pattern involves the expansion of parks from single protected areas into constellations of large, connected, contiguous areas. Each of the parks explored here (and we only feature six of the hundreds of possible parks) resides in a neighborhood filled with similar sites. Sometimes these are national parks from another country, other times they are reserves for native peoples, or areas with different conservation protections. To talk about Peru’s Manu National Park then is to also imply that Alto Purus National Park, the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, and the Los Amigos Conservation Concession share a connected history with the original park. These constellations and their growth and dynamism matters to understanding how parks are created and what they mean to different kinds of people. Parks, their names, their designations, and their dilemmas change over time and this contingency forms an important—but slippery—part of their story.

This website invites you to choose your own explanations based on historical data. Explore the comparative biographical statistics on the parks—their dates of creation, sizes, neighbors, and remarkable features. Then listen to scientists and conservationists provide testimony in their own words about their interest in national parks and why these places matter. Travel through the timeline looking at different primary sources that provide glimpses of the parks from earlier times. When you are finished, leave us a line letting us know what you learned.