Manu

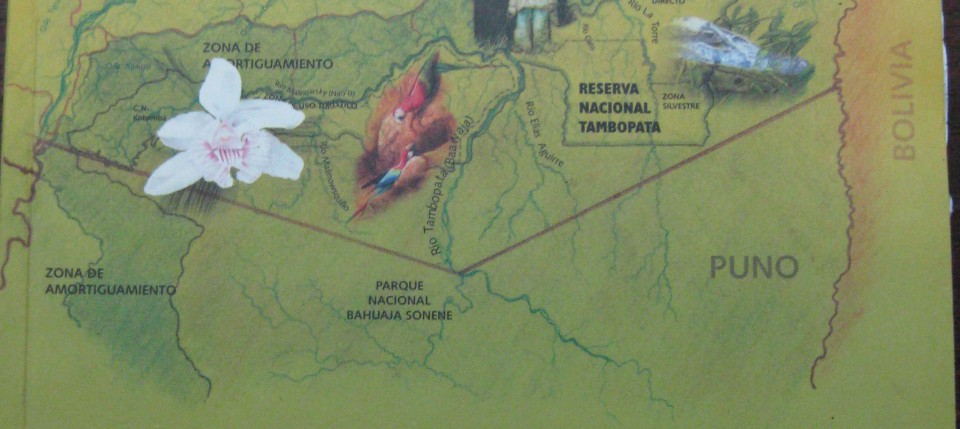

- Location: Departments of Cusco and Madre de Dios

- Size: 17,160.36 km2 (6,626.65 sq mi)

- Established: Proposed 1968, Declared May 29, 1973, UNESCO World Heritage, 1987

- Coordinates: 11°51′23″S 71°43′17″W

- Contents: Madre de Dios and Manu Rivers, range of ecological zones from cloud forest to lowlands, highest biodiversity in the world

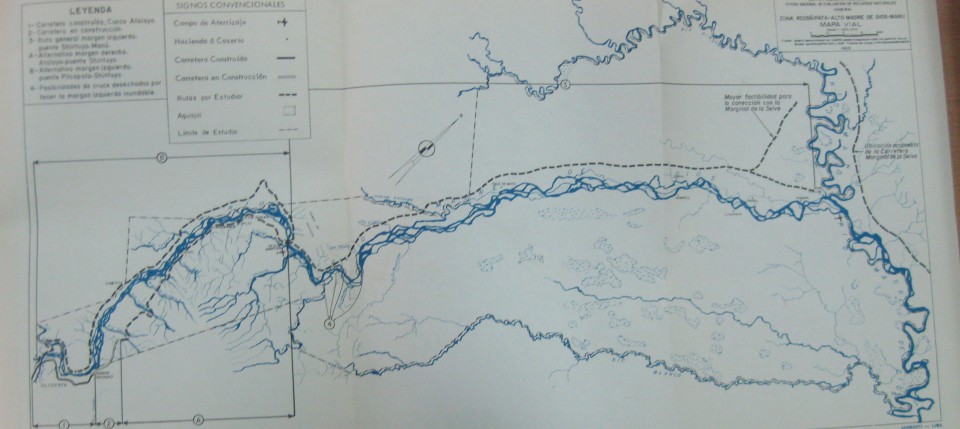

Located in the far western Amazon basin and the Peruvian departments of Madre de Dios and Cusco, the park was officially created by the Peruvian government in 1973. It is widely recognized in international ecological circles for the field-changing science emerged from the location and for the remarkably intact ecosystems ranging up the Andean slope and down into the tropical lowlands. The region is characterized by rivers which serve as the only transportation channels for most of the park.

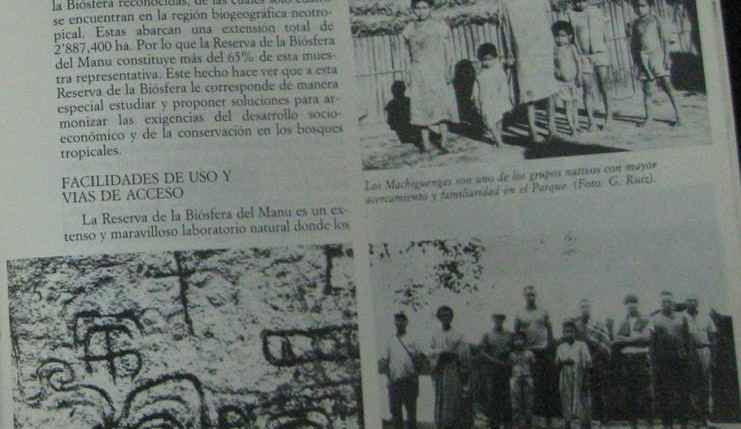

Long before its creation as a National Park the region was lauded with superlatives. The superlatives come in three general varieties—geographic, scientific, or cultural. The geographical statistics point out the size, siting, or the remoteness of the site. These include descriptions of the lack of services including roads and supplies. Scientific statistics come next and these provide an overview of the numbers of species, the comparative percentages of the world’s stock these include, and the relationship to biodiversity. The remaining superlatives and statistics describe the cultural contradictions embodied in the park, describe or illustrate the living communities of indigenous people, especially the Matsigenka, within the park.

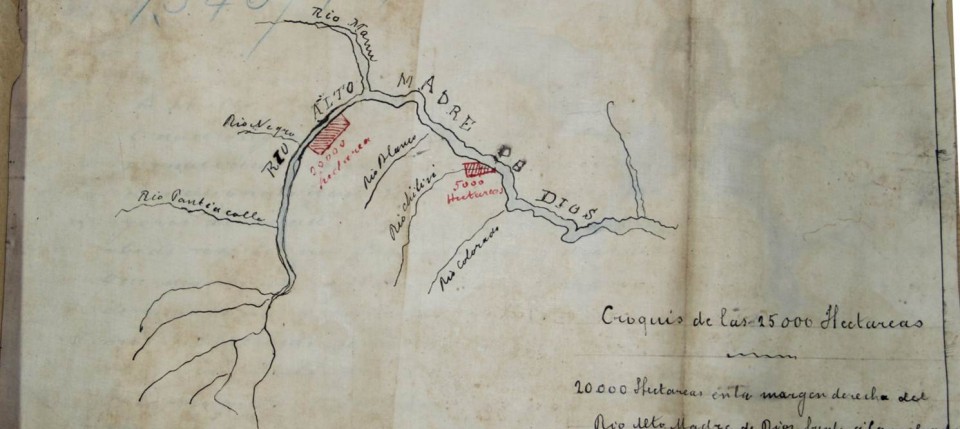

The park’s area has never been empty of human habitation or modern designs but it remains one of the foremost examples of wild nature in the world because of the density and scale of self-willed land in and around the park. From rubber to gold to oil, various schemes have been developed to bleed the jungle of its riches with adverse effects on the residents or native peoples. But the park has thus far remained resilient and demonstrates an excellent example of the scale necessary to allow nature to rebound and recover from overuse.

Consider how these documents testify to the use and nonuse of nature within the park. First, look at the map of land concessions to consider how rubber prospectors envisioned making their mark on the region. Then consider the fate of the region in the images and newspaper article forty years later. What changed? Now turn to the development map planning a road through the region. You may wonder how this supports or refutes earlier development schemes. Reconsider the park timeline as you reflect on the next set of three maps of the research station at Cocha Cashu. Consider how the trails at the station change over time and the difference in scale from the first two maps. Finally, examine the description and pictures of residents in the park provided by the Peruvian researcher in the 1980s.